Experience Yesterday's World of Tomorrow Today with Go!

Experience Yesterday's World of Tomorrow Today with Go!

Foreward by a Future Version Of Myself

Hi. The following is basically some vaguely incoherent thoughts I have had about computer history while mucking about with Go on OpenBSD and Plan 9. The usefulness of the included information may vary, as the only time I seem to be able to write blog posts without being interrupted is between midnight and 3am. Enjoy!

Go where at least one language has gone before

I’ve been getting into Go recently. Google’s Go, not the other one. The reason is simple: I’ve been working in some weird operating systems due to a frankly unhealthy interest with OpenBSD and Plan9.

Shout out to OpenBSD, btw. You should totally install it somewhere and use it for fun development projects. It works really well, and has probably the best man pages ever. Also it is paranoid tier secure against several attack strategies and just feels very Computing (as opposed to current OSs). I do this callout because I’m about to talk about Plan 9 a lot and I don’t want OpenBSD to appear like an also-ran, it’s probably the more useable of the two.

Bonus points: LLMs have no idea how these OSs work, so using OpenBSD for your hobbies in this world of rapidly increasing AI usage is like having a little safe timeout space where you can practice your craft. How exciting!

… Uh… Where was I? Oh, right.

Rust, the language I was most recently working with, appears to be very closely tied to Linux/Mac/Windows. Now, that doesn’t mean you can’t write programs in Rust on OpenBSD for example, but because there are a lot of libraries that depend on libraries that depend on C integrations with the underlying OS… it’s fairly common to import a package or attempt to build a project only to find it fails because your platform is not supported. This is actually not as bad as you might think and I’m not complaining, this is what I would expect.

What I don’t expect is that Go just… kind of works.

As a result, I’m writing a lot of Go. And Go, if you’ve used it, is boring. Which is a plus, it’s trying to be boring to reduce the complexity of the language. It’s also garbage collected, which usually means you’ve got a VM in the way. And while that can be fast, I really don’t like having virtual environments between me and the hardware. Imagine my surprise when I learnt that Go is not running on a VM!

Go actually has several interesting features:

- Go has a full framework written in Go that provides all the base language components that any program needs

- Go absolutely refuses to do dynamic linking, all compilation is statically linked. This allows a program to run without needing Go installed, in fact with nothing but the underlying OS, Go’s framework talks to the OS exclusively through syscalls.

- Go’s network stack, garbage collector, thread scheduler and synchronisation system… everything, comes with that framework. Meaning that the GC has more in common with the Boehm GC for C than the Java or C# GC. There is no VM!

- Go isn’t big on sharing memory. In Go you share by communicating via channels. This has always reminded me of Ada’s rendezvous feature, and is a far less chaotic way of linking up programs and threads than using memmaps and mutexing. If you’ve ever had to deal with a multi-process threading synchronisation feature, you’ll already know how a pair of pipes can outperform a memmap in terms of orderly management of data.

But after poking around on my more esoteric OS’s, I’ve noticed that there are some curious similarities. Okay more than similarities, significant resemblances. Okay no, it’s just Plan 9 C II: The Return Of Actual Usage.

The heck is Plan 9 C?

Okay if you’re a massive nerd (or are just, you know, old), you’ll already know where I’m going. And I get it, you know this, why would anyone be excited etc etc…

Listen. Some people don’t know, yeah? Alright here we go.

Some History

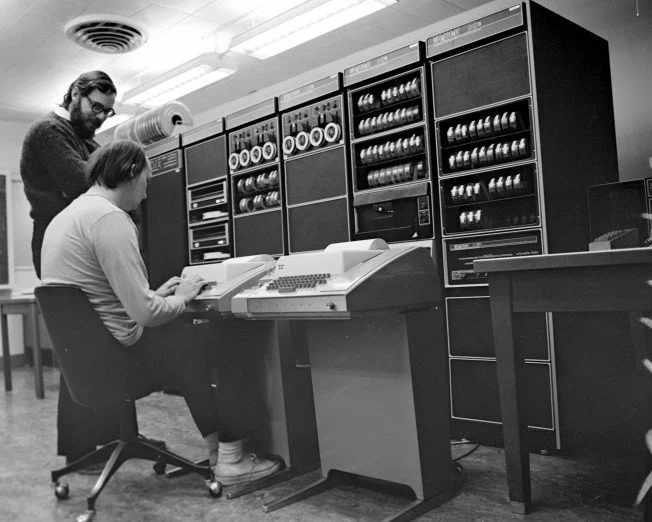

Yall heard ‘bout UNIX? Lots of people know about Linux, some people might even think Linux is UNIX. But it isn’t! UNIX was an operating system created back in the never never by the two Nerdiest Dudes On The Block, Ken Thompson and Dennis Richie. You can tell they’re the biggest nerds around cause of their Impressive Beards. There were several others but we’re focusing on these two for narrative reasons, go read the wiki. Yeah anyway Ken had a game he wanted to play (a space simulator, man after my own heart) on the PDP machines they were using to write MULTICS, a ludicrously complex multi user multi tasking operating system they were building for Bell Labs at the time. Believe it or not they finished MULTICS, and it went on to basically be a footnote in computer history. MULTICS stood for Multiplexed Information and Computing System, and was designed for mainframes with many terminals, thus the multiplexing. The OS that Ken et al ended up building was designed for a single system without said multiplexing i as a resultnitially, and was given the delightful name Uniplexed Information and Computing System, or UNICS. This was, for whatever reason, eventually changed to UNIX.

Now I love that story because it invokes the vibes of my time in late undergrad, hanging out with a bunch of other students in computer labs and getting lost in mad side projects. It just so happens that that side project turned into the future of computinis Whoops, I guess.

Anyway then the crystal cracked and Unix was split into the Mystics and the Skeksis BSD and AT&T Unix. One of the things important to note about the difference between the Unix family and Linux is that Linux is not the same thing, because of what you got with BSD or System V Unix. Both the kernel and the userspace tools came with the Unixes — that’s why BSD stands for Berkely Software Distribution, it’s a whole bunch of software and the core Kernel. Linux is only the kernel, it needs the GNU userspace tools to be a whole OS. Now you know why it’s called GNU/Linux.

You still have no idea what this has to do with Plan 9, don’t worry we’re getting there. All of the tools that made up the Unix OS, and the kernel, are all built in the language C. C was also developed by Ken and Dennis while building Unix. The decisions made with C were broadly to do with the intents and limitations of the systems Unix was built for. For example the systems generally had little storage, so several versions of a compiled library was not a great idea. Thus, dynamic linking is kind of the standard. The downside of this is that you can rapidly enter dependency hell, where multiple programs depend on different versions of a library and they expect them all to be the same file name… which doesn’t really work. This wasn’t an issue back when you had one machine running Unix and you compiled everything for that machine on that machine… but as soon as Unix made it to smaller computers like PCs, distributing software and porting between environments became extremely hard. It’s still hard, distributing executables that are precompiled require complex package dependency systems, and when that fails we resort to packaging entire userspaces in appimages, flatpaks, or docker images.

There are several of these problems with the Unix setup that cropped up fairly quickly. Soon after it really got going commercially things like “networks” cropped up, and suddenly the assumptions made about how Unix would be used basically imploded. So the remaining research team behind Unix then tried to peer into the future and develop the next idea in computer systems. In doing this, they decided to build things in a way that would fix the issues they now knew existed in the design of Unix. They also had freedom to really experiment, so they basically went and built a totally cracked OS. This was Plan 9 From Bell Labs.

Plan 9 From Bell Labs

Now Plan 9 was basically the idea of Unix + a network taken to the logical conclusion. In Unix, everything was a file (well, mostly). In Plan 9, everything was a conversation with a remote file server. Unix assumed that everything was going to happen on the same machine, Plan 9 assumed “hey, if we’ve got several machines in a network, who is to say that they aren’t all part of the same system?“. What if one machine was the CPU, another was the file system, your laptop was just the terminal, and somewhere else was the… uh… other file server? Look there weren’t that many component types, they just could be put anywhere, not on just one machine. Application servers for business software, archival storage servers, everyone’s terminal, all as one massive system. It truly was the Grid from the original Tron.

To pull this off, Plan 9 needed to have a means by which to make remote access of files and processes functionally equivalent to accessing local stuff. This took the form of 9P, a multiplexing file access protocol that bound all of the individual machines in the Plan 9 system together. In addition, IO inside individual machines were also performed using 9P. The kernel was basically just a local 9P client! This consequentially is where the /proc/ folder came from in Linux, borrowed from Plan 9. In Linux it’s a handy way of getting info on processes, in Plan 9 it was the only coherent way of monitoring and interacting with processes that may be resident across several CPU servers.

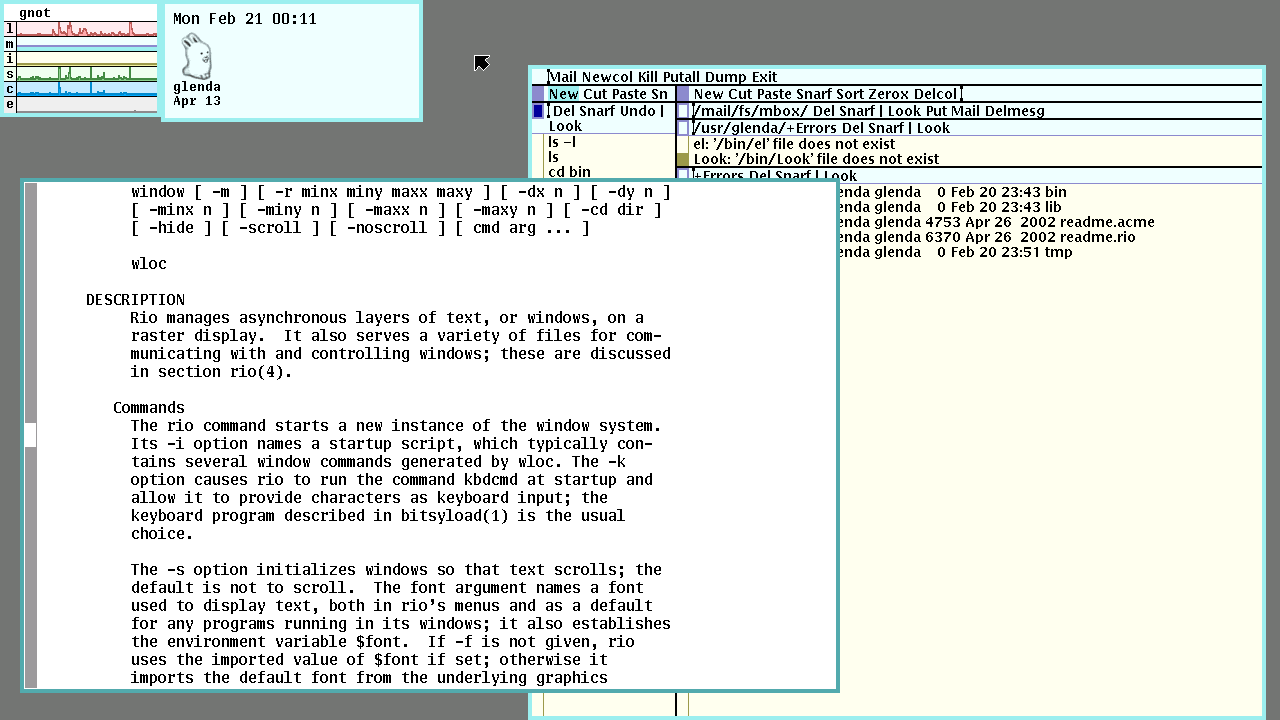

Other wacky choices that make sense in retrospect include the complete elimination of the console as an initial startup environment. Instead, you get Rio (pictured above), which is a full windowing environment. This may seem normal with MacOS and Windows having done this for decades by now, however back in 1992 this was a huuuge leap. Another choice? There’s no root like you know it. Because the system may be on many machines, there is a second “filesystem owner” account named glenda. Which also happens to be the name of the delightful rabbit mascot above!

Speaking of processes across several machines, how do you make that work when the shared libraries may be across the network? Well ahhh… you just don’t have them. Yes in Plan 9, there were no shared libraries. Everything was statically compiled. That way all you need is the executable, and it brings the whole world it needs to execute with it! This is actually where that deployment strategy is from, and this should sound vaguely familiar…

The Plan 9 C Dialect

Anyway, Plan 9 was also all in C. But a better C, a newer C, a C with nicer function signatures and a radically simplified library structure. Let me give you an idea:

This is hello world in C:

#include <stdio.h>

int main(int argc, char **argv) {

printf("Hello world!\n");

return 0;

}Seen it before, very boring, etc. Well, here’s what you get in Plan 9 C:

#include <u.h>

#include <libc.h>

void

main()

{

print("Hello world!\n");

exits(0);

}Firstly, you’ve got two includes. u.h is an architecture specific header that defines types and other base components per architecture, and libc.h contains… an entire libc header. No need for stdio, and stdlib, and string, and math, and what have you… it’s all there in libc! main is also a void returning function that exits with an errorcode of 0.

Plan 9 C also has some cool features that derive from the OS. Because all kernel operations are basically file operations via a remote file protocol, there’s no real reason to use kernel multiprocessing unless you absolutely need to do things at the same time. Any kernel request will essentially sleep the calling thread until the response is ready. This means that userspace threading (green threading, if you will) is the way to go most of the time. Also to keep with the general theme of single means of doing things, Plan 9 C uses channels and a kind of operating system rendezvous to perform IPC. You can still use real processes, and pipes, and even shared memory (it’s how the rendezvous system is implemented between real processes), but these new ideas are here… and if you’ve used Go, you’ll know these concepts already.

Oh hey, and also you can do this:

#include <u.h>

#include <libc.h>

void

main()

{

pointer_value = some_function();

if (pointer_value == nil) {

print("error occur\n");

exits(1);

}

exits(0);

}nil? Oh yeah that’s what Plan 9 C calls NULL, because it makes slightly more sense. This pattern will be incredibly familiar if you’ve ever written any Go before.

So yeah it’s a better C. A cooler C. A C++ if you will (even though someone else had already got to that name). And it should be pretty clear now that it’s basically the direct precursor to Go.

Go is just Plan 9 but for Real People

So uhhhh the guys who developed Go right? Ken Thompson, Rob Pike, Robert Griesemer? Two of those guys, Ken and Rob, were core to the Plan 9 team (and Ken is obviously core to, you know, Unix as well). Go is specifically designed to bring as many of the good ideas of Plan 9’s programming environment to the rest of the world as possible, whilst reflecting the fact that Plan 9 was (while ahead of it’s time) completely wrong in how it guessed the future would look. PCs ate the entire computing market, the future was the internet. So, Go is just “What would Plan 9’s C environment look like if it had the constraints of the Internet?”

Firstly, Plan 9 C (and Unix C for that matter) were designed with the idea that the programs wouldn’t be running long. A few hours at most if you were playing games. Most stuff was run on demand by users and would shut down, daemon services just redirected user (and later external) requests to short lived tools that produced a response. The idea that a web server would be a fantastically complicated VM that would need to run forever was not in the world at this point. Memory management and program stability requirements change dramatically when execution lifetime disappears into infinity. Go, therefore, uses a garbage collector that is bound into the Go framework. You’ve gotta use Go to malloc and free anyway, it’s not using libc or stdlib or whatever you have lying around… so wrapping all memory usage in a smart GC is rather easy. Even with the Boehm GC you’ve got to consistently use it when you are allocating to get the benefits, Go just makes it impossible to not use the GC.

Plan 9 also allowed you to specify interactions between processes or threads sort of freehand to allow you to tune in the amount of parallelism vs concurrency you were getting. Go recognises that this is a minefield for long running applications and instead demands you as the user only use user threads. It then schedules them across Go processes that allow it to take maximum use of the processor. Go also borrows Plan 9’s rendezvous system in the form of channels, and then makes them the defacto way of synchronising and communicating between threads. In a doubly-fun trick, this means that the inter-thread communication occurs exclusively userspace-side, meaning that there’s no mucking about with IPC.

Go still brings along the idea of static compilation, and will compile the whole Go framework and any library you import into the final executable. This has all the same benefits as Plan 9’s “you just copy the executable” strategy, but also means that in a world where processor flaws mean we spend more and more time in the space between user memory and kernel memory to prevent someone reading everything via speculative execution, less of the Go program itself has to pause and be dependent on the kernel interrupt. This is because the entire user program is always dependent on the Go framework which is always in userspace. Go’s framework can then itself determine how to schedule and manage IO and interrupt waiting. This may sound kinda boring but it is huge for speed, especially in OpenBSD where jumping from userspace to kernelspace involves the most complicated memory shenanigans you can imagine. Rust programs can run so much slower than Go programs in such an environment.

Go’s other big win above Plan 9 C is that it’s not dependent on Plan 9. Plan 9 C kind of requires Plan 9, the u.h thing almost mandates it. Go is self contained, and written in Go. It is only dependent on an operating system specific shim that gives the Go framework access to OS specific syscalls. This means that Go is one of the few modern languages that works on Plan 9! Sure enough, Go has first class support for Plan 9, just don’t use cgo because that won’t fly. But that means you can slap Go programs after compilation into an extremely barren userspace and it’ll just kinda work.

Oh and if you still thought this was a coincidence, the Go gopher was drawn by the same artist, Renee French, who drew Glenda the rabbit mascot for Plan 9.

Wait, what was the point of this again?

Look I tried Go when it first came out. I was there! Sure I was in undergrad and I’d only just really got a handle on C, but I still tried it. I didn’t understand the lack of pointer math and got annoyed and tossed it.

Not my proudest day, but it was a new language and I was learning a lot at the time.

Today, I still don’t like Go, but for specific aesthetic reasons. I like optional datatypes, like the way Swift or Rust handle it. The fact that I have to keep going thing,err := maybe_error() drives me a little batty. Some people don’t like error being a kind of string, I don’t really care honestly. I don’t like that Go allows both var thing int = 1 and int := 1, it should choose one and invalidate the other. Extending that, const blah int = 1 is also a bit bonkers, I’d expect something like const blah := 1 to be enforced. Come to think of it, var thing int is a bit redundant, why can’t we use thing int? But I digress.

The point is that it’s a good language. It’s got things a lot of other languages don’t, history. A veritable cavalcade of things that have been tried and improved upon, from B to C and Unix to C in Plan 9 and on to the various revisions of Go. It is extremely well thought out for modern development, and it works really, really well. All things you can not say about Node.js. Or most other languages, really.

Also, the point is that you should try installing Plan 9. Or it’s mad and twisted fork 9Front. Learn yourself some computer history.